The perfect boiled egg is often shrouded in mystery and conflicting advice – old eggs, fresh eggs, room temperature, fridge temperature, boiling water, residual heat…so many variables, so much CONFUSION! And what makes it worse, is that eggs are covered in a hard opaque exterior, the shell, that is, preventing us from truly understanding what’s going on inside the damn things.

Well never fear! Because me – and my apparent insomnia – is here to help! We’ve done the experiments, so you don’t have to. Here’s how to get perfectly boiled eggs.

Method and First Notes

I’ve done many MANY more experiments than this, but because of a recent marathon of Good Eats, I’ve decided to also try Alton Brown’s kettle method. This is where you place 4 eggs in your electric kettle, cover with about an inch of water, and put the kettle on to boil. Once the water reaches boiling point, it will shut itself off, leaving your eggs to cook only in residual heat.

For the purposes of this experiment, I’ve used fresh, free-range eggs from the fridge, because let’s face it: most people keep their eggs in the fridge, and to bring them to room temperature in the morning before breakfast, on top of all the cooking techniques, is just too much work.

The most important thing to note at this point, is that the vigorous boiling of the water actually caused the eggs to bounce around violently inside the kettle, resulting in cracks, and white bits floating around in the water. Sexy. I know that this isn’t because of the shock of cold eggs hitting hot water, because the eggs were first covered in cold tap water before it was brought to the boil.

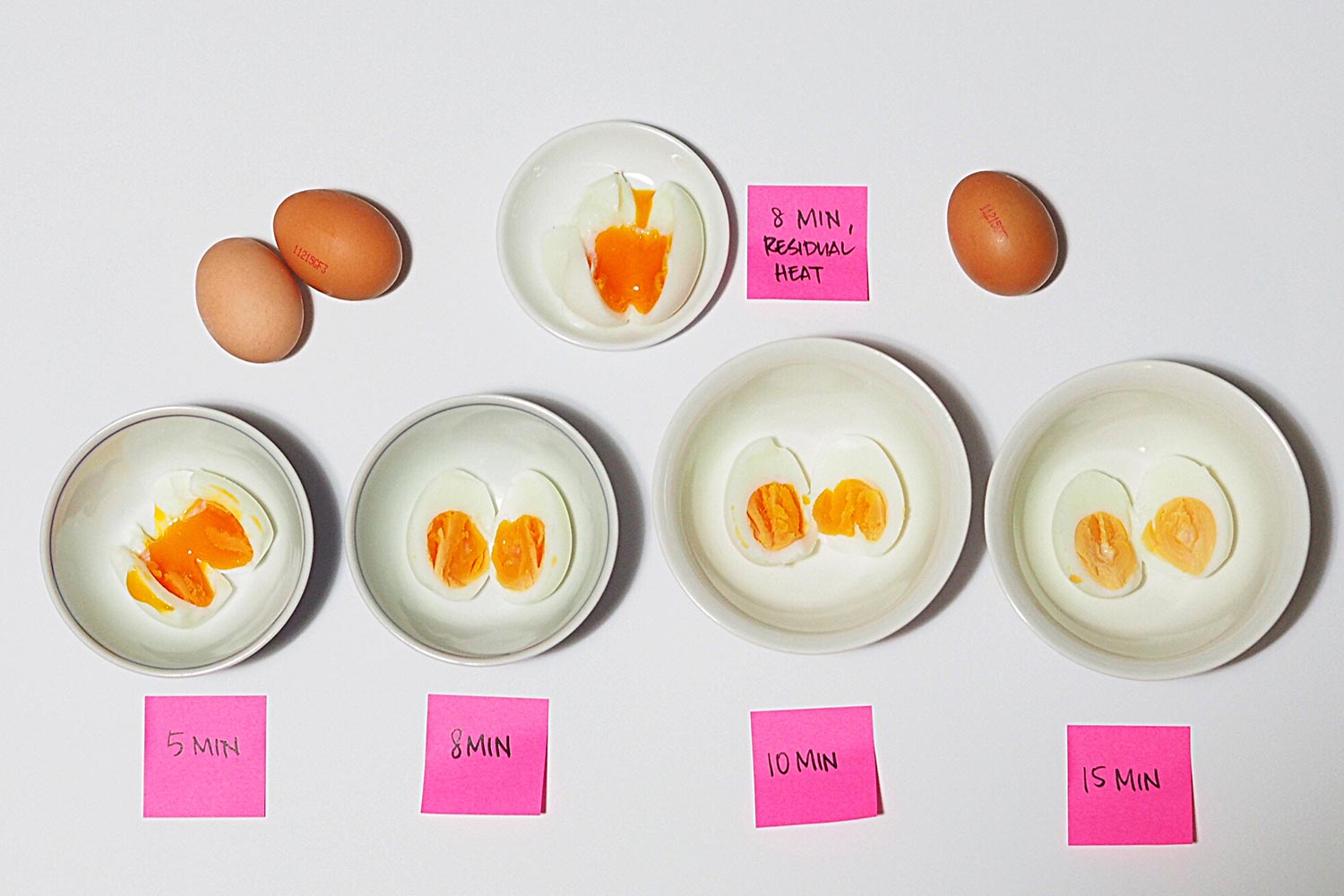

Once the kettle clicks off, I set my timer for 5, 8, 10, and 15 minutes. Once the time has passed, I took the egg out with a pair of tongs, and ran it under cold tap water to stop it from cooking any further. I set this aside and label it, and once all the eggs are done, I then peel them all, and cut them, to prevent the eggs from prematurely drying out.

5 minutes

This produced a fairly soft boiled yolk, and tender whites. As you can see, the yolk started to firm up around the edges, but you still get your #yolkporn if you so desired. The egg was fairly difficult to peel, mostly because it was so soft in the middle. The egg threatened to split in two the moment I tapped it on the counter to crack the shell, and there was some sticking of the membrane, resulting in small chunks of delicious egg getting torn off in the peeling process.

8 minutes

The 8 minute mark is where I would start calling an egg hard boiled. The egg is cooked enough for the yolk to be completely set, but with a texture that is slightly more creamy than powdery still. Personally, this is where I would stop if I wanted hard boiled eggs say, for a potato salad or a Caesar salad, but only because powdery egg yolks bring back bad memories for me.

10 minutes

This egg is what most people would imagine the typical hard-boiled egg to be. White and yolk is firmly set, allowing you to get a clean cut with a knife. This is where Alton tells you to stop if you want a hard boiled egg, using this method.

15 minutes

So what if you left it another 5 minutes? Well since the direct heat has been turned off, it takes longer to overcook an egg than you would think. The yolks are definitely cooked all the way through, no two ways about it, but it’s still lacking the telltale grey ring around the yolk that is a sure sign of an overcooked hard boiled egg. Not bad.

Bonus Easter Egg! Geddit?

Because boiling your eggs in a kettle might not be such a great idea if you also want tea with your breakfast, I thought it might be a good idea to see what happened when you put the egg in after you’ve turned off the heat. This means that you can bring a pot of water to boil on the stove, and then lower the egg in carefully and cover. In this case, I left it in the water for 8 minutes, and it produced a slightly softer, runnier result – both with the white and the yolk – than the 5 minute egg from before.

Final Notes and Conclusion

So how DO you get the perfectly boiled egg? Well I’m not a fan of this kettle method at all, since it messed up the inside of my kettle, and prevents me from getting my cup of tea. Instead I use these timings with a cold, 60g (large), free range egg from the fridge, set into rapidly boiling water:

5 minutes, with 30 sec residual heat – soft boiled egg for soldiers to be dunked into.

6 minutes 30 seconds – for set whites and liquid yolks, perfect for marinated eggs to top a ramen.

8 minutes 30 seconds – hard boiled. For salads, and other hard boiled egg needs.

Eggs age 7 times faster outside of the fridge than in (apparently!) and I’m really not up for bringing my eggs to room temperature before breakfast and tea. Not happening in my house. So I think it’s perfectly fine to cook the eggs from the fridge. In fact, for set whites and liquid yolks, it’s essential that the eggs are from the fridge, or you’ll get slightly runny whites or slightly set yolks. Not what we want.

Now there have been concerns that the cold eggs will crack the moment they hit the boiling hot water, and to that, I say it’s so very important to get free range eggs. And no, it’s not a moral issue. Free range eggs, I’ve found, have thicker shells, and this will help prevent the cracking and tell-tale signs of escaping white. Also, if your eggs are fresh, the whites are less watery, meaning that you don’t get quite as much fallout, even if your eggs do crack.

The other reason why it cracks, is also because some people drop the eggs into the pot of water with their fingers. So I mean DROP, literally. The weight of the egg causes enough impact for the shell to crack, and that doesn’t help anyone. What I like to do is use a soup spoon – long handles! – or a pair of tongs to lower the eggs into the water carefully. Set your timer, and bring the water back to the boil quickly, and you have predictably cooked eggs every time.

Also, the reason why older eggs are easier to peel – older eggs are higher in alkalinity, and the age also causes the membrane to separate slightly, allowing you to easily peel your eggs. I don’t know about you, but I’m not waiting a couple of weeks just to eat my boiled eggs, so there are a couple of ways to counter this. Food geek legend Harold Mcgee says to add baking soda to the water to increase the alkalinity. But really, by dropping the eggs into boiling water, the shock of heat helps the membrane separate anyway, making it easy to peel.

And finally, whether you’re cooking it at a rolling boil or not, I don’t really taste a discernible texture difference regarding how rubbery whites can get if they’re overcooked. Unless you’re hellbent on overcooking your eggs, I don’t think that water at a rolling boil is going to affect it that much, except give you more time in the morning!

Do you have any egg questions? I’d love to help out! Just leave me a comment below.

What a fun little eggs-periment! I love the residential heat 8 minute egg – I’m always a fan of a runny yolk!

Well, this is a very comprehensive test. I don’t think I’d ever put them in my kettle, cups of tea are far too important to me.

I know, right! Apparently Americans don’t rely as much on the electric kettle, which is probably why Alton thought it’s a good idea.

thanks for posting this up :). my stove is a bit run down so it takes longer to boil the egg for me